DSPORT Issue #224

Text by Michael Ferrara

Take two nearly identical vehicles equipped with the same drivetrain, brakes, suspension and aero. Set both vehicles to have the same exact final weight and weight balance. If the only difference is the rigidity of the chassis, do you think it will make a difference on the race track or the street? Ask any experienced race car builder or even OEM vehicle designer and the answer will be a definitive “yes.” All other factors being equal, the higher the rigidity of the chassis, the quicker the car will be around a racetrack. If that’s not reason enough to consider improving the rigidity of your project car’s chassis, consider that vehicle control will also benefit, as well as the overall safety of the vehicle.

Why Go Stiff?

So the promise of better performance, improved vehicle control and increased safety warrants attention, but just how does a more rigid chassis make all that happen? Quite simply, a rigid chassis provides a more stable foundation for your vehicle’s suspension. By minimizing the flex in the chassis, the suspension takes control of keeping the tires in contact with the road surface. When there is flex in the chassis, the chassis itself works as an unpredictable fifth spring in your suspension. This flexing of the chassis can create a vehicle that stores and releases the energy stored in the sprung chassis at the least opportune moments. The end effect is a vehicle that exhibits delayed steering response, reduced cornering ability and sometimes a mind of its own. When a chassis flexes during cornering, this flex can pull the steering components to affect the alignment toe settings. These changes in toe can actually steer the vehicle, giving it the mind of its own attitude. To compensate for the flex-induced changes to suspension alignment, the driver must counter the resulting chassis steer scrubbing away speed. Of course, a car that steers on its own also decreases the driver’s control of the vehicle and its overall safety.

Making it Stiff: Starting Point

Once convinced that increased chassis rigidity is desirable, the next logical step is to explore how to make the chassis more rigid. All of today’s performance vehicles are built on a “unibody” design, as opposed to the body-over-frame design that was used almost exclusively up through the 1950s and 1960s. With a unibody, the body or shell of the vehicle functions as the frame and structure for the vehicle. The design of the roof, floor, pillars and accompanying chassis bracing all affect the chassis rigidity of the vehicle. As computer modeling, metallurgy and manufacturing techniques continue to advance, nearly every new generation of a vehicle is able to be touted as having a double-digit increase in chassis rigidity. Hence, the first step is to start with the most rigid chassis that you can find to build upon.

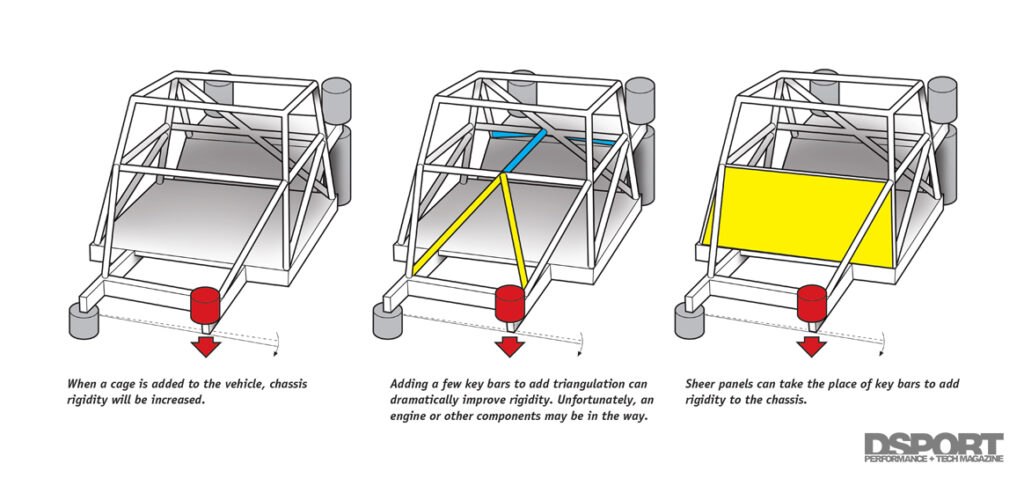

The Triangle Offense

The geometric reality of increased rigidity is usually found in the shape of a triangle. The triangle represents the simplest, lightest and most rigid frame structure. In both nature and construction, examples of triangles make up rigid structures. Whether the component is a roll bar or a simple strut tower brace, the use of triangle geometry provides peak rigidity increases for minimal weight.

Practical Street Solutions

A weld-in roll cage or stitch welding the chassis are proven ways to increase the rigidity of a chassis. However, neither is practical for most street cars. Instead, practical solutions come in the form of “bolt-on” strut tower braces, chassis braces and bolt-in roll bars.

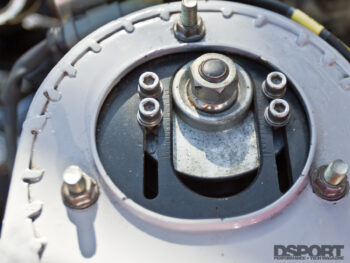

The simplest strut tower brace simply connects the left and right strut towers with a rigid link that significantly reduces the flex of the tops of the strut tower. This flex normally occurs when only one of the two front or rear wheels encounters a bump that drives a force up through the strut toward the top of the strut tower as the spring and damper are compressed. Without a strut tower brace in place, the result is that the top of the strut tower flexes closer to the opposite strut tower during this compression phase. The flexing of the chassis also stores energy which is release when the suspension rebounds to keep the wheel in contact with the road on the backside of the bump. Here the tower may move further away from the other tower during this rebound. This movement in the shock tower can cause other steering links and suspension members to move affecting alignment and steering. Hence, the basic strut tower brace accomplishes a great deal, despite its simple design. More complicated strut tower braces that not only tie the strut towers together, but also triangulate the brace to the firewall, improve chassis rigidity by reducing the maximum deflection of the portion of the chassis between the firewall and the shock tower.

Under-chassis braces include lower tie bars, sub-frame braces and ladder braces. The purpose of many of these braces is to improve the rigidity of the suspension member mounting point. Since all forces applied to the chassis enter through the suspension and sub frame, increasing the rigidity of the mounting points often pays big dividends. The lattice design of most sub-frame braces helps to reduce the flex that the sub frame, the chassis and the point at which they join experience. Lower tie bars also supplement the sub frame by joining the pivot points of the lower suspension arms, eliminating yet another variable from the suspension geometry puzzle. Though not as popular as strut tower braces or chassis braces, the installation of aftermarket fender braces in front of the door hinges underneath the front fenders can also help to eliminate flex.

Last, but not least, a properly designed bolt-in roll bar or roll cage can also increase chassis rigidity. However, most serious performance enthusiasts view bolt-in roll cages as they do two-inch harnesses. Both are half-ass solutions. If you are going to live with the inconvenience to entry and egress that a roll bar or cage exhibits, simply get a custom weld-in cage that fits your vehicle and the type of motorsport that you enjoy.

Full-Race Recommendations

There are no serious race vehicles without a weld-in roll cage. Properly designed to meet the specifications provided by the sanctioning body of the motorsport, a weld-in full cage will significantly increase chassis rigidity while also providing additional driver safety in the event of a roll over or crash. If you are building a racecar from the ground up, you may also want to consider stitch welding or riveting the entire unibody structure. Stitch welding or riveting the overlapping seams of metal will increase the overall rigidity of the chassis without adding any additional weight.

Maximizing Torsional Rigidity

Attend a “long-lead” or read a press release when a new generation of vehicle is released and you will always hear “The new chassis has a XX-percent increase in torsional rigidity.” Instead of saying “That’s impressive,” the more common response is to simply think “So what?” While 99-percent of automotive buyers understand the advantage of more power, nearly the same percentage wouldn’t be able to tell you the advantage of having a chassis with increased torsional rigidity. In reality, significant increases in the torsional rigidity of a chassis should be a reason for celebration.

Terminology: Rigidity, not Stiffness

Years ago, torsional rigidity was often referred to as torsional stiffness. Both refer to the same properties of the chassis. Unfortunately, this nomenclature caused some confusion since many often use the term “stiff” to describe the unfavorable ride quality of a vehicle. In reality, increasing the torsional rigidity of a vehicle improves ride comfort quality by allowing the suspension to work more efficiently.

Torsion

When you look up the definition for torsion, you’ll inevitable start getting the shaft. That is to say, they’ll talk about how torsion is the twisting of an object (usually a shaft as the example) due to an external or applied torque. When you apply a torque to a shaft the shape of the shaft, its cross-sectional area and the modulus of rigidity of its material will dictate how much it twists for a given amount of torque. Circular or round shafts will have a lower angle of twist in torsion than a square, all other factors being equal. A shaft that has a diameter that is double the size of another will have just 1/16th of the twist angle as the smaller diameter shaft. As for material, a material with twice the modulus of rigidity will only twist half as much.

When a sanctioning body specifies a tube for a roll bar or roll cage, they will often specify the bar diameter, material and the method of welding. For example, to build an NHRA legal roll cage, a 1.625” diameter bar must be used. A thicker 0.118” mild steel (10XX series) can be used or a thinner 0.083” 4130-alloy “chromoly” material can be used. According to NHRA rules, mild steel can be MIG-welded but the alloy steel requires TIG-welding. Using the 4130-alloy steel with the thinner wall thickness provides 35% weight savings over the thicker mild steel. Both have comparable torsional rigidity. While all of the material is round tubing, it’s interesting to see how the diameter, wall thickness, material and welding method all influence its ultimate performance.

Torsional Rigidity

Suspension guru Herb Adams (author of Chassis Engineering) defined torsional rigidity (actually “stiffness” in his 1993 publication) as it applies to a vehicle’s chassis as “how much a frame will flex as it’s loaded when one front wheel is up and the other front wheel is down while the rear of the car is held level.” Herb paints a picture that is easy to see while he goes on to say, “This condition is seen at every corner of the road, so its importance to proper handling should be obvious.” While it may have been obvious to some OEM manufacturers and racecar builders, increasing the torsional rigidity of a vehicle without significantly increasing the weight is the engineering challenge.

Fortunately, advances in computer chassis modeling, higher-strength materials, new welding techniques and superior bonding materials are allowing both OEMs and racecar builders to build vehicles that sport far more torsional rigidity than cars of the past. Whereas, a 1966 ford Mustang coupe probably had a spec around 5,000 Nm per degree, today’s 2015 Mustang is well over 20,000 Nm/degree. What’s the high-end of current automobile technology? A Bugatti Veyron claims a torsional rigidity over 60,000 Nm/deg.

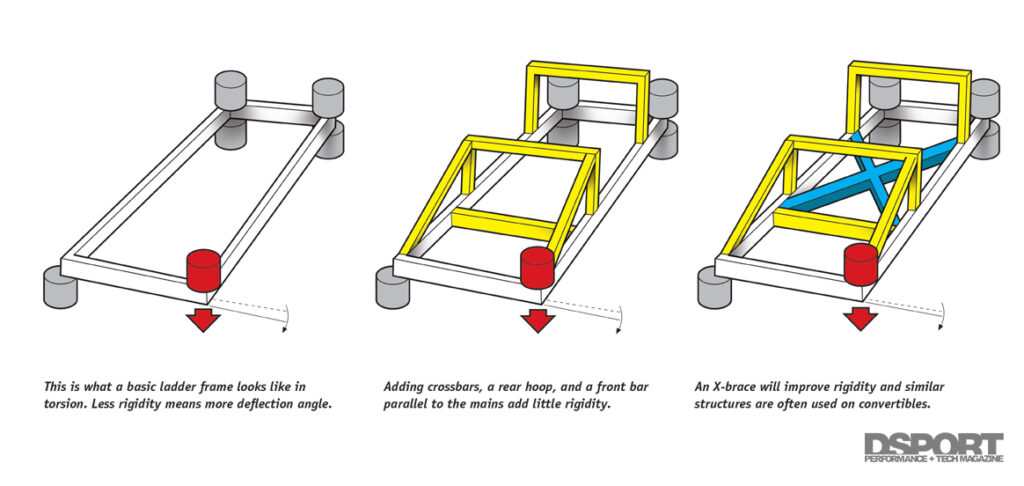

Why Convertibles Suck…

Take any coupe or sedan with an impressive torsional rigidity and turn it into a convertible and you’ll be lucky to get half of what you had. Even after the factory adds weight with X-beam supports under the floor, there is still no substitute for a roof when it comes to stiffening up the chassis. A Porsche 911 (996 variety) drops from 27,000 Nm/deg to just 11,600 Nm/deg when you compare the coupe to the convertible.

Advantages of Increased Torsional Rigidity

In the simplest terms, vehicles that have high torsional rigidity deliver a superior ride, superior handling and better response to driver input. Improving the torsional rigidity of a vehicle allows the suspension to work more efficiently and predictably. Vehicles with high torsional rigidity will see more travel in the suspension, as the chassis isn’t moving. Considering the suspension uses dampers and the chassis doesn’t, it makes sense why you want the suspension to move and not the chassis.

The chassis and suspension of a vehicle can be thought of as five independent sets of springs. There are the two front springs, the two rear springs and the chassis that acts as a fifth spring. If we cut a car down the middle and only look at what happens to a single spring in the front and rear along with the chassis, we are able to consider a three-spring model. When three springs are put in series, the force or load across the springs is equal. The weakest spring in the series will still deflect the most for a given load even if the other two springs are upgraded to a higher rate (stiffness). This is why some vehicles do not respond favorably to high-rate springs unless the chassis rigidity is improved first. Finally, increased torsional rigidity decreases rattles, squeaks and vibrations.

Improving Torsional Rigidity: OEM

On the OEM side, manufacturers are turning to using higher-modulus (stiffness) steels, additional welding and the latest high-strength bonding adhesives to improve torsional rigidity. While adding torsional rigidity is easy if weight is added to a vehicle, it’s a real challenge when adding additional weight is not an option. Today’s fuel efficiency standards force OEMs to think twice before adding weight to a vehicle.

Improving Torsional Rigidity: Street Aftermarket

For a streetcar, we’ll consider solutions that can be bolted in place. When it comes to a bolt-on solution, triangles and X-designs are usually evident in the products that actually work. So first, look for solutions made of high stiffness materials that incorporate those geometries. When you find products that may actually have been engineered and manufactured to work properly, the second step is to address the chassis as three independent structures: front, center and rear. This is the exact approach that Lexus engineers took in putting together the RCF. The front is anything up to the firewall, the middle is the firewall back to the rear seat and the rear is the back of the rear seats to the end of the vehicle.

A triangulated front strut tower brace that ties into the firewall may improve the torsional stiffness of the chassis on the order of 10-percent. For example, the OEM tower brace on a 2015 Mustang convertibles adds a full 10-percent to the torsional rigidity. In contrast, a front strut tower brace that is not triangulated back to the firewall may only offer a 1- to 5-percent improvement. As for lower front bracing, braces that simply run from side to side will not do much of anything. However, braces that form an X between the two “frame rails” will improve torsional rigidity. There is often very little available for the center section of the vehicle in terms of bolt-on bracing. Harness bars that bolt to the factory belt mounts do not accomplish much. As for the rear of the vehicle, the same rules apply as the front. Strut tower braces are more effect when tied to a bulkhead (unfortunately most vehicles don’t have a fixed rear bulkhead).

Improving Torsional Rigidity: Cages, Stitch Welding

If you really want to improve the rigidity of a vehicle and you have no objections to adding a roll cage, you’ll be stoked with the results. Even street cars that add a weld-in roll bar or roll cage can see dramatic improvements in ride quality, handling and even 60-foot times. However, not all bars and cages are created equal. If the main hoop simply has one horizontal crossbar, you won’t see much of a gain. Add a pair of bars down to the transmission tunnel area from where the crossbar intersects with the main hoop and you have magic.

If you have the opportunity to strip off the paint of the vehicle you may also want to explore the merits of stitch welding. By stitch welding overlapping panels that are only factory spot welded (or worse yet not bonded together), chassis rigidity can be increased. One of the most critical areas is the firewall (which is essentially a shear plate when the chassis is in torsion). Stitch welding this area can show the best increases in rigidity.

The Bottom Line

The more rigid the chassis, the quicker it will be on the track or at the strip. In addition, improving chassis rigidity will make for a vehicle that will be easier to control as the suspension is able to do its job with maximum efficiency and predictability. From first-hand experience, we’ve witnessed the improvements with everything from a simple set of front and rear strut tower braces to a weld-in roll cage. A vehicle with improved chassis rigidity simply becomes more enjoyable to drive as it responds better to driver input while requiring less driving effort. Of course, one must consider an ultimate limit to chassis rigidity. Can a chassis be tweaked to be too rigid? Probably not. Chances are that none of the recommendations provided in this story would take it too far, so plan your strategy accordingly. Remember that the chassis is the backbone of the vehicle that provides the foundation for every other system on the vehicle. While aftermarket performance braces don’t show a performance improvement that’s easily verified on a dyno, they can often be felt in normal street driving or verified on a timed road course.

Finally, designing and building a chassis with maximum torsional rigidity and minimum weight is the desire of every chassis engineer. Advances in materials and manufacturing have allowed automakers to make vehicles that offer four to 10 times the chassis rigidity of cars built 30 years ago. While we cannot always afford the best chassis as a starting point, there are bolt-on and weld-in solutions for significantly increasing the chassis rigidity of the vehicle. In the coming months, we’ll demonstrate how to measure and gauge improvements to the torsional rigidity of a chassis on a future project car build.