It’s a little-known fact that the “end bug” at the end of every story ever written in DSPORT is the tip of a hardness tester. Specifically, the shape follows the indenter used for Rockwell C testing. We came up with the name Hard Media to describe the audience and goal of the content that we produce for DSPORT. A hardcore audience of enthusiasts looking for hard facts that allow hard decisions to be made about purchasing performance products. We’ve never shied away from explaining the “hardest” topics to our readership. For a metallurgist, hardness takes on a more specific meaning. Hardness is the material’s resistance to penetration. Rockwell, Brinell and Vickers machines represent the conventional testing processes that measure the size or depth of an indention made on a test piece of material after a specific load was placed on the material for a set amount of time. While these tests are valuable tools in the engineer’s arsenal, they are far from being practical in the field. All these tests require a test sample of the material that can fit in the machine. Hence, they do not allow for direct testing of a component in its final form in most cases. Fortunately, there is a portable hardness testing option that can be used to test just about any object that weighs over two pounds.

Text by Michael Ferrara // Photos by Joe Singleton

DSPORT Issue #212

The Harder, the Better?

What are the benefits of having a harder material? The most basic benefit of using a harder material is that it will have a higher resistance to abrasion and wear than a material with a lower hardness. You may remember the elementary school science test that talked about Mohs scale of mineral hardness where talc was rated at 1 and a diamond at 10. You could find the Mohs hardness of a material by seeing which mineral was able to scratch the other. If you were busy eating paste in elementary school then perhaps you caught our YouTube video with Driven Racing Oil. In this video, we explored the effects of material hardness and surface finish on wear. You may remember that the camshaft with the harder material showed considerably less wear than the camshaft with the lower hardness rating after undergoing the same test cycle on the engine dyno.

This Barcol Impressor was our tool of choice for aluminum hardness testing.

What is Hardness?

A material’s hardness isn’t a fundamental property. Instead, a material’s hardness is simply how a certain material responds to a particular test. A material that registers a 100 rating on a Rockwell B test (1/16” ball at 100kg) might show a rating of 24 on the Rockwell C scale (120-degree cone at 150kg). This same material might show a 526 reading on the HLD scale. There exist no mathematical equations to transfer one scale to another. All the conversion charts that exist are the result of experimental evaluation. The only way to compare the hardness of two different samples is to compare them on the same scale.

Our Rockwell Hardness tester is still called into service to make hardness measurements. Unfortunately, it’s only capable of testing components that can fit into the machine.

If it’s Harder…

It is well known that the harder the material, the smaller the size of an indentation you can make on the material with a given amount of pressure. If you took a soft piece of wood, like a balsa wood, or maybe even a piece of Styrofoam, these soft materials would allow you to make quite a sizable indentation by simply pressing firmly with your thumb. If you took similar objects made of a harder wood (ash, oak, birch) or a piece of metal and pressed your thumb with the same amount of pressure as you used on the balsa wood, the size of the indentation (if there would be one at all) would be significantly smaller on the harder material. The Rockwell, Brinell, and Vickers tests all use the same basic principal. The differences are mainly in the type of tool used to make the indent and the amount of force applied. We have a Rockwell hardness tester at Club DSPORT that we use whenever we need to check the hardness of a material. Unfortunately, the Rockwell tester cannot accommodate larger items. We also use a Barcol Impressor to test the hardness of aluminum parts like cylinder heads and blocks. This is a very handy tool that keeps us from wasting time on an aluminum cylinder block or cylinder head that has gone soft. Unfortunately, the Barcol Impressor cannot be used on harder metals like cast-iron or steel.

It is well known that the harder the material, the smaller the size of an indentation you can make on the material with a given amount of pressure. If you took a soft piece of wood, like a balsa wood, or maybe even a piece of Styrofoam, these soft materials would allow you to make quite a sizable indentation by simply pressing firmly with your thumb. If you took similar objects made of a harder wood (ash, oak, birch) or a piece of metal and pressed your thumb with the same amount of pressure as you used on the balsa wood, the size of the indentation (if there would be one at all) would be significantly smaller on the harder material. The Rockwell, Brinell, and Vickers tests all use the same basic principal. The differences are mainly in the type of tool used to make the indent and the amount of force applied. We have a Rockwell hardness tester at Club DSPORT that we use whenever we need to check the hardness of a material. Unfortunately, the Rockwell tester cannot accommodate larger items. We also use a Barcol Impressor to test the hardness of aluminum parts like cylinder heads and blocks. This is a very handy tool that keeps us from wasting time on an aluminum cylinder block or cylinder head that has gone soft. Unfortunately, the Barcol Impressor cannot be used on harder metals like cast-iron or steel.

Leeb it Alone

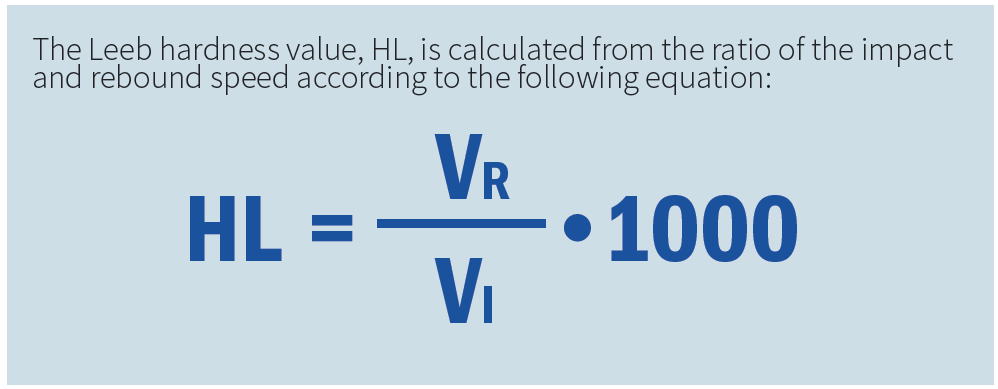

In 1975, the Leeb hardness test was introduced. This hardness test used a different characteristic of a material’s hardness. It was noticed that when an object hits a harder surface, it rebounds at a much faster speed than when it hit a softer object. The Leeb hardness test calculates and expresses the hardness as the quotient of the rebound velocity to the impact velocity times 1,000. Materials receiving a higher Hardness Leeb D-scale (HLD) reading would be harder than one receiving a lower HLD reading. This is the science behind the majority of the portable hardness testers used in the field today. While some units use other methods, this Leeb rebound technology delivers a method that can be used on an extreme variety of materials.

Starrett 3811A Hardness Tester

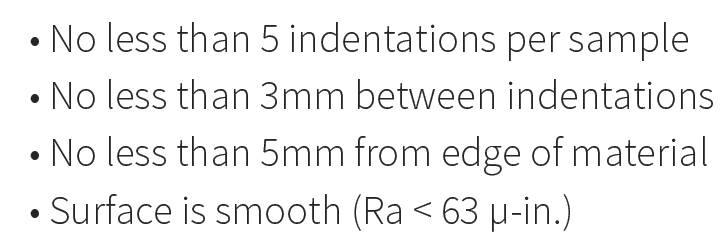

Accurate to 0.5% and repeatable to +/- 4 units on the HL scale, the Starrett 3811A Compact Hardness Tester provides an easy way to measure the relative hardness of large parts. The system includes the measuring unit, a D-type impact device, a calibrated test block, case, cleaning brush and a manual. The D-type impact device allows use on a variety of materials including tool steel, stainless steel, cast steel, grey cast iron, ductile iron, cast aluminum, bronze, brass and wrought copper alloy. The system is very easy to use. After looking over the manual, we were taking measurements. To get accurate and repeatable readings, the manual suggests:

Since the Leeb scale isn’t used as much as other scales, the Starrett 3811A lets you select the type of material you are testing so that it can provide an equivalent Vickers, Shore, Brinell or Rockwell (B or C) hardness value. If you work with steels, the 3811A can also be switched into strength mode and give you relative strength ratings of the steels. If you are going to be testing a large number of sample (or you just like to keep everything organized), you can tether the 3811A to a laptop and run the included software to record all of the measurements.

Linking up the Starrett 3811A to a laptop allows the data from all measurements to be seen graphically and stored in a much more organized fashion. Here you see the five samples taken along with the average result.

Practical Applications

What are some practical applications for a Starrett 3811A portable hardness tester? First, we have found that this unit can completely replace the Barcol Impressor. Now, instead of using the delicate Impressor, the substantially more robust Starrett 3811A Portable Hardness Tester can be used to determine if aluminum cylinder heads or aluminum cylinder blocks have gone soft (occurs when heads and blocks are severely overheated). Second, we no longer have to guess if the scrap piece of aluminum that we are purchasing is 6061 or 7075. We simply check the Leeb hardness and we know for sure. This is also handy around the shop when we need to identify a particular material. Third, we can use the Starrett 3811A Portable Hardness Tester on parts before and after they are sent out for heat treatment (or if we heat treat them ourselves). Fourth, checking the hardness of a material before a machining operation may allow for the selection of a more appropriate cutting insert or a proper setting of the feed and speed. Finally, it can be used to track the change in hardness of a part while in service. In fact, we will be using this hardness tester to compare the hardness of cryo-processed brake rotors versus standard brake rotors during the service life.

We are seeing that the Starrett 3811A can be a complete replacement for our Barcol Impressor on aluminum cylinder heads and blocks.

The Bottom Line

The more you know, the better the decision you can make. Being armed with a Starrett 3811A allows us to know more about the condition of used parts before we begin machining operations. An aluminum block that is too soft may allow aftermarket sleeves to sink over time. An aluminum cylinder head that has lost its hardness may have valve seats that recess into the cylinder head. Identifying unmarked materials is also a practical use of the Starrett 3811A. In this way you can be sure to use 6061 aluminum on a project that will be welded or 7075 on a project that is going to be tapped. Now for our first official testing with our new compact hardness tester, we will pull out all of the RB and 2JZ blocks we have on hand and take some measurements.

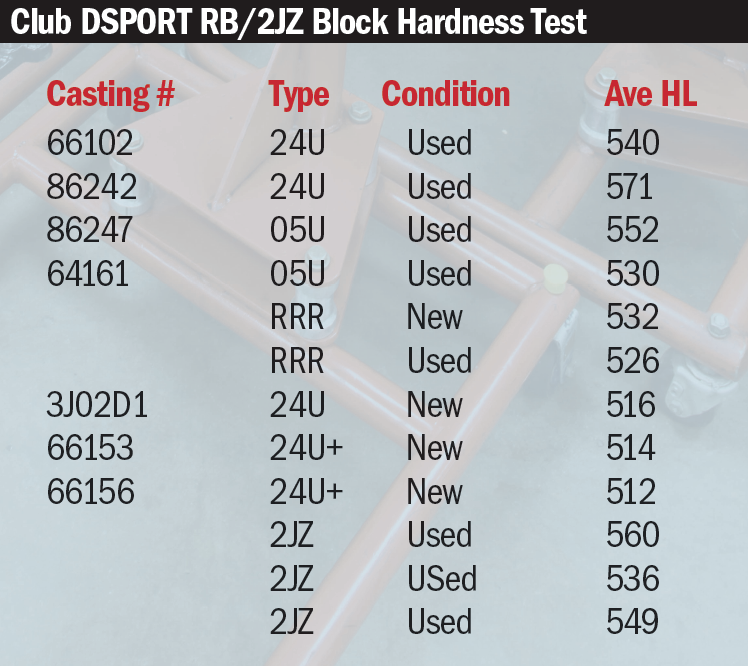

RB26 and 2JZ Block Hardness Test Nine RB26 and Three 2JZ Blocks

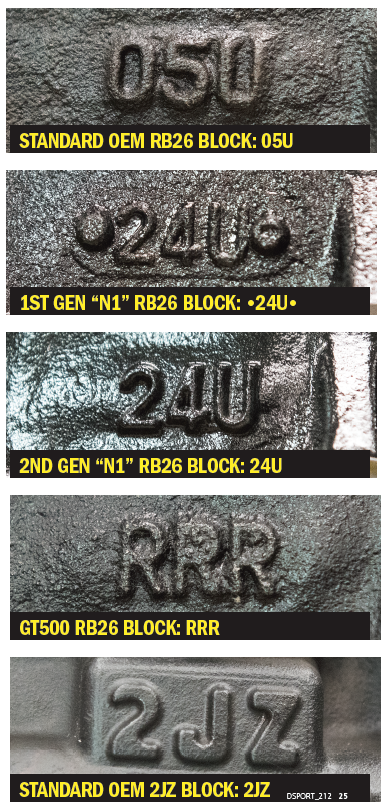

Almost three years ago (Issue #181), we sonic-checked the RB26 blocks we had on hand (Standard 05U, N1 24U, N1 24U second-gen, and RRR) to see how the cylinder wall thicknesses varied from block to block. This article inspired the guys at Motive DVD and Platinum Racing Products to put together a YouTube video last year titled “Which RB block is best? Mythbusted with Facts and Data.” While we were flattered to have inspired a YouTube video that garnered over 135K views, something didn’t seem quite right with some of the conclusions. I really wasn’t sure what it was, but I figured that we have a decent number of RB and 2JZ blocks at Club DSPORT, so let’s try the same test. In conducting the test on our own, we found some interesting trends that don’t support the conclusions made by the Motive/Platinum YouTube video.

Wrong Setting

The hardness testing done on the blocks in the video did not have the material-type set properly to correctly display the Brinell hardness values. The material setting was on “0” (Steel and Cast Steel), whereas it should have been set to material “3” (Gray cast iron). Since the display was showing the equivalent Brinell hardness values, these values are all off. We confirmed this with our tester when the same block tested a 235 Brinell with the tester set to “steel” or a 200 Brinell with the tester set to “gray cast iron.” Based on what we seen, all the testing was done by Platinum Racing Products with the incorrect settings. While this might sound like the worst-case scenario, it’s not that bad. Since all the data was obtained with the wrong settings, it can at least be compared to other data taken with the same wrong settings. Hence, the relative differences still apply, but the data in terms of equivalent Brinell hardness values is way off.

New vs. Used Blocks

While the tester setting was an easy oversight, testing new blocks (N1 and RRR) versus used blocks may not be fair based on our own findings. Granted we only had four new RB blocks and five used RB blocks on hand to test (we will from now on test every block and add them to our database), but there was a definite difference in hardness between new and used engine blocks. On average, the used blocks measured 544 while the new blocks averaged 519. Our lowest hardness blocks were the brand-new N1 blocks (one first generation, two second generation). These measured an average Leeb Hardness of 514. But before you discount the N1 blocks, consider that two used N1 blocks showed the highest average Leeb Hardness (556). In fact, one of the two N1 blocks checked in with an average Leeb Hardness of 571, which was the highest value of all the blocks tested. While the Platinum Racing Products found the RRR blocks to be soft, our new example checked in at 532, the highest mark of all the new blocks.

Better with Age

Many engine builders hold to the belief that starting with a used cast-iron engine block is better than starting with a new block. While artificial aging does result in gray cast iron becoming harder and stronger, we haven’t run a test to prove that an engine block gets harder and stronger after being in regular use. Our small sample indicates that the aging that occurs in normal use likely increases the hardness of an engine block, but it’s too small of a sample to draw a conclusion from. Still, it would be best to compare new blocks to new blocks and used blocks to used blocks before any conclusions are made.

Gray Area

Cast iron engine blocks are made from gray cast iron. Gray cast iron has graphite molecules that have the shape of flakes. When fractured, the site of the break is along these embedded graphite flakes. Gray cast iron gets its name from the characteristically gray color that appears on the surface of the fracture. Gray cast iron is superior to other types of cast iron in terms of damping (20-to-25 times that of steel), ease of machining and wear resistance. It falls short compared to other cast irons in terms of tensile strength and ductility.

Just the Facts

We tested nine RB26 engine blocks and three 2JZ engine blocks. All the 2JZ blocks were used while five out of the nine RB26 blocks were used. All three new N1 engine blocks tested at a lower hardness compared to the used N1 engine blocks. The new RRR block tested higher than the new N1 blocks. The new RRR block also tested higher than the used RRR block. As for the RB versus 2JZ debate, the average hardness for the five used RB blocks and the three used 2JZ blocks was identical. Based on the data from our sample group, we could draw the exact opposite conclusions as those drawn in the Motive/Platinum video in terms of average block hardness levels. So, who is right? DSPORT of course! But seriously, there is a good chance that the sample blocks tested by Platinum Racing Products did exhibit the trends that they observed. However, we got results that were about 180 degrees opposite. Ultimately, the hardness of an engine block goes beyond what three numbers or letters are cast in the side of the block. Casting, by nature is a somewhat inexact science. Small variances in material composition, temperature of the mold, cooling temperatures, tempering and artificial aging cycles will all affect a block’s hardness. The block’s life after it leaves the foundry also seems to affect its hardness. Bottom line is that if you need to know, take the measurement.