DSPORT IS NOW 100 ISSUES OLD and while we would normally take advantage of such a moment to complain about how old we have all gotten, we’ll reflect on the past instead. Thrice before, we have published retrospectives about DSPORT and its place in the industry. Most titles never turn a profit and fail within a few issues. Fewer still manage to become acknowledged leaders in the industry. And although our long-term readers have lived much of this history with us, we would like to share our story with the thousands of readers who have joined us along the way.

By Ryan Beck

Originally Published in Issue #100 of DSPORT

DSPORT’s Backstory

The history of DSPORT began long before we published the first issue. In 1984, Kipp Kington presaged the growth of an import-tuning scene in the US. In that year he had a revolutionary idea: there must be people in the US interested in learning more about turbocharged-vehicle performance. Months later, Turbo & High-Tech Performance launched its first issue in July 1985. A small but loyal cult following soon began to grow.

Meanwhile, domestic manufacturers were also dabbling with forced induction and turbo power. Despite phenomenal advances in performance, turbocharged cars (even Buick’s now legendary 3.8-liter turbocharged V6 Grand National) were still barely known within the performance community. Kipp and his editors pioneered the first magazine that recognized performance vehicles from all countries of origin while showcasing modern technologies such as turbocharging, electronic fuel injection, and centrifugal supercharging.

In 1994, the future publisher of DSPORT magazine, Michael Ferrara, turned down higher-paying, “real” engineering jobs out of college for the opportunity to become technical editor for Kipp’s magazine. Sure, the job was half the pay, but it offered Michael the opportunity to dive into a subject that he loved. Soon after he joined the magazine, the scope of the magazine shifted from a 50/50 balance of domestics and imports to a 90/10 split in favor of import performance. “It was by no means a master plan. My friends were all driving imports. Very few people had a clue or understanding about import performance. It was time that someone pushed for serious progress to be made,” said Michael. “In 1994, there were no experts to turn to for advice. If you called ACCEL and asked about installing a DFI engine management on a Honda, the tech would tell you that you needed to get a GM four-cylinder distributor to make it work. Fortunately, we knew enough to know that the tech was dead wrong. Soon after, we wired up the first aftermarket engine management system on a turbocharged Honda. Playing with more boost pressure and more power, we soon found the limit of stock pistons and connecting rods on the D16 engine,” says Ferrara.

Meanwhile, the street racers of Southern California prodded Eddie “The Power Doctor” Kim of Dynamic Autosports to carry more performance parts. Kim delivered on the challenge as Dynamic Autosports became the first shop to stock the hard-core, engine performance parts from JE Pistons and Crower Cams as well as the parts offered by Japan’s full-line tuners HKS, TRUST (GReddy), and others.

The Import Tuning Field Gets Crowded

Less than an hour’s drive away, another publisher began to focus on import performance with the launch of Sport Compact Car (SCC). Originally, the title debuted as a Mini-Truckin’ for cars. It contained the worst-of-theworst cars that could be found on the street. The name of the magazine, selected to ensure Ford’s advertising support for the book, was as bad as the cars inside. In the original Sport Compact Car, the feature cars were hacked and ugly. However, the content of the magazine and its direction soon changed. An aggressive advertising salesman by the name of Tony Mercadafe and an editor by the name of Larry Savedra began to make SCC a true player. With the addition of Technical Editor Dave Coleman, SCC could finally be taken seriously.

With two magazines focused on the same potential enthusiast, a rivalry between Turbo and SCC developed. Every month, each magazine tried to outdo the other. SCC was soon outselling Turbo on the newsstand thanks to better distribution. In an ironic twist, the industry perception was that Turbo was bigger than SCC. Greg Gill (the VP of McMullen Argus, publishers of SCC at that time) said, “we would be in a meeting with the NHRA and they would be telling me that Turbo was the better selling book. It was crazy. SCC was outselling Turbo by two or three to one. Yet they had the NHRA and others convinced that Turbo was outselling SCC. The guys at Turbo were doing a much better job of self-promotion.”

Competition in the import enthusiast area soon got even more intense when Petersen Publishing launched Super Street in 1997. Initial sales of Super Street agreed with SCC’s and Turbo’s assessment that the new magazine was a joke. However, in just a year after launch, Super Street began to grow. Turbo and SCC now realized that Super Street was indeed a threat. “Both SCC and Turbo were focused in the mid-to-late 90s at being the performance leaders. Super Street was taking the low road; covering the basics while spreading the ‘it’s fun to fix-up your car’ message. The editors at Super Street didn’t know that much about performance, and they didn’t pretend to either,” says Ferrara.

Super Street’s success proved that an entry-level performance community existed and was looking for information. Back at IGC, the publisher of Turbo magazine, the management knew that a decision had to be made. Either Turbo would have to broaden its scope to address the entry-level enthusiast, or it would need to launch a new magazine to compete with Super Street. In response, IGC’s Associate Publisher Michael Ferrara planned the launch of a new title, Import Tuner. However, the IGC staff was divided on the need for another import performance title. “We had the resources and talents to launch a magazine that would take the industry by storm. Kevin Convertito was a talented artist that could bring a whole new magazine design to the performance arena. Rich Convertito, Kevin’s Dad, was a seasoned veteran of newsstand distribution. Edward Eng had the ability to spot feature vehicles that the enthusiasts wanted to see. As for myself, I was willing to do whatever it took to launch the new title. However, other members of IGC’s staff did not agree that Import Tuner was a viable expansion. In particular, the bulk of the sales staff believed that a title directed at European car performance should be launched instead. As a result, I ended up wearing the ad sales hat to make sure we had the advertising revenue that we needed to launch the new title,” explains Ferrara.

In 1998, the original Import Tuner launched with unprecedented success. Providing useful tech to the entry-level enthusiasts was exactly what the industry needed. Later, under the editorial direction of Edward Eng, much of the focus changed from performance to show. While showcasing show cars was not the original intent of the title, the growing show community gave tremendous support to Import Tuner and its new direction.

Import Racing Takes Off

In the few months prior to the launch of Import Tuner, a group of thirteen racers, tuners, and manufacturers established the Import Drag Racing Circuit, Inc. to take the sport of import drag racing to a national level. Unknown to those involved at the time, the import drag racing circuit would eventually lead to the creation of DSPORT magazine. “At the time, Frank Choi and Battle of the Imports were considered the leaders in the import performance events arena. A few promoters had done some local events, while entrepreneur Gene Wong had created the National Import Racing Association (NIRA) in Northern California. We felt that Battle of the Imports was limited as its events were only held in Southern California. NIRA was also limited due to a lack of connection with the racers and a lack of technical knowledge. Something had to be done. That’s what prompted the formation of the Import Drag Racing Circuit, Inc (IDRC). We believed there was a need for a racing organization that was made up of racers looking to take import racing to the next level,” says former IDRC National Director Peter Hipolito. He continues, “the next level came as we took the racing to a national level bringing the best cars from the West to the East coast for the 1998 IDRC East Coast Finals. The following year we teamed with the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) to produce a pair of events. Everything seemed in place for import racing to truly take off.”

The IDRC & NHRA’s Short-Lived Romance

During the 1999 season, the momentum of import drag racing seemed unstoppable. The NHRA needed to address its future. Because the average age of the spectators at NHRA events increased every year, the NHRA needed a plan besides coffin seating. A relationship with the IDRC seemed an ideal marriage to expand the sport to a younger audience, and the two teamed together to produce a pair of events. “We were bringing our experience and relationships with the racers and it was our hope that NHRA would be bringing the major sponsor dollars that would take the sport to the next level,” says Peter. However, the additional sponsor dollars never materialized, and the relationship came to an end when NHRA attempted to negotiate an agreement with NIRA (the IDRC’s biggest competitor which was now owned by Petersen Publishing, the producers of Super Street Magazine) without informing the IDRC of its plans. “I’m bound by contract to not put any blame on the NHRA for the way they handled themselves during our business relationship. However I don’t think I’ll be sued for saying that I wish things turned out differently and that matters would have been handled differently,” says former IDRC National Director Michael Ferrara.

While the IRDC dealt with the loss of its partner, significant changes were shaking up the publishing world. McMullen/Argus (PRIMEDIA) purchaseed Turbo and Import Tuner from IGC and Kipp Kington. PRIMEDIA now owned three of the four major import performance titles (SCC, Turbo and Import Tuner). For the staff of IGC, the ownership change was disastrous. The head count dropped from 33 employees to just a dozen survivors. The newly acquired staffers from IGC and the high-quality titles that they brought with them were treated like red-headed stepchildren by PRIMEDIA. The PRIMEDIA sales staff continued to hustle SCC, the magazine that they knew and loved, while Turbo and Import Tuner suffered. “It wasn’t that surprising that the transition had issues. Sport Compact Car and Turbo magazine had a rivalry for close to ten years at the time. We didn’t like them too much and they didn’t like us too much at first,” says former Import Tuner Editor Edward Eng.

The PRIMEDIA Monopoly

In 2001, the stage was set for further consolidation both within magazines and import racing series. In August, PRIMEDIA acquired EMAP, the publishers of Super Street, completing its monopoly of the four largest important performance titles. As expected with any monopoly, advertising prices in the four titles increased, burdening the performance industry with higher advertising rates just as the economy dipped into recession. Shortly after the merger, PRIMEDIA and the NHRA made an announcement at the 2001 SEMA show in the fall that the NHRA had acquired NIRA. Only insiders knew what really happened: PRIMEDIA had gained control of NIRA with the acquisition of EMAP. Since NIRA was not a profit center, it was bartered away in a deal with the NHRA.

DRAGSport is Born

The start of 2002 looked to be a great year for import drag racing. The IDRC had signed Auto Trader to a three-year contract as the title sponsor, and the merger of the NHRA and NIRA provided a consolidation that promised to favor the racers. Finally, the Nopi Drag Racing Association (NDRA) entered into the fray. Together, the three series offered more events and more prize money to the racers than ever before. As for the publications, PRIMEDIA was selling more subscriptions and single copies than ever for their titles. However, the PRIMEDIA titles were providing less coverage to import drag racing. Bad weather and a saturated event schedule meant that both attendance and coverage for import racing events in 2002 were down. In addition, the effects of 9/11 terrorist attacks and a weak economy meant fewer sponsorship dollars for everyone. In June of 2002, the IDRC decided that something needed to be done to support the racers. Plans were put in place for a “National Dragster”-type magazine for the import racing community. The magazine would be called DRAG Sport.

ISSUES #1-to-#13 DRAG Sport

PRIMEDIA Declares War

Before the first issue of DRAG Sport was created, the IDRC met with PRIMEDIA to discuss the plan for DRAG Sport: the IDRC events would promote the PRIMEDIA titles (Sport Compact Car, Turbo, Import Tuner) and, in return, PRIMEDIA titles would support the series with coverage and promotion. Since PRIMEDIA controlled the majority of the press at the time, the IDRC didn’t wish to upset PRIMEDIA and lose its magazine support of its IDRC events. DRAG Sport was designed from the start as a partner rather than competitor to PRIMEDIA’s offerings. Drag Sport was meant to be the “National Dragster” publication for the import drag racing community that would help to direct its members and readers to the PRIMEDIA titles through subscription advertisements in DRAG Sport. The magazine’s targeted distribution to nearly 1,000 import tuning shops from coast to coast and its tabloid, large-format of the magazine were chosen to avoid cannibalizing PRIMEDIA’s sales.

After the first issue of DRAG Sport was in print, the powers at PRIMEDIA decided that DRAG Sport was not a partner but a competitor to the PRIMEDIA titles and the “treaty” was broken. Quite simply, DRAG Sport ended up being considerably more successful than PRIMEDIA ever imagined. DRAG Sport was an instant success that pulled great response from both advertisers and readers. However, in the eyes of PRIMEDIA, DRAG Sport was a little too successful for their liking. The first issue of DRAG Sport had come out of the gate with advertising support that frankly had PRIMEDIA very concerned. Under PRIMEDIA’s control, the once-great Turbo magazine had dwindled in circulation, advertiser support and industry relevance. DRAG Sport had inadvertently provided the outlet that serious performance parts manufacturers were looking for but not finding in the PRIMEDIA publications. As a result, PRIMEDIA ceased to promote or cover IDRC events. At that time, the IDRC events were the only revenue stream to keep the staff of the IDRC employed. This wasn’t a simple slap in the face; it was a kick in the balls that sparked a heated rivalry with PRIMEDIA that lasted until the company dumped its performance titles in 2007.

TRADERS

Two thousand three presented a series of challenges to the IDRC and to the magazine that it had spawned. The crises began early in the year. After missing its scheduled sponsorship payment in January, Auto Trader prematurely exited from its business relationship with the IDRC. The circuit was left with a balance of nearly $190,000 in championship payouts for the 2002 season along with a scheduled $100,000 in guaranteed championship payouts for the 2003 season without the backing of a series sponsor. “The beginning of 2003 marked a low-point for the IDRC racing series. We had been committed to supporting the racers from day one, but we had overpledged and overcommitted to resources which ended up vanishing in a flash. Accountants were advising bankruptcy for the events division, but as racers ourselves, we never wanted to take this easy route. Instead, we leveraged personal assets and emphasized the growth of the publishing division,” says Michael Ferrara. Ferrara continues, “Obviously everyone wants to get paid on time and that was our plan with the championship payouts. We screwed up by not having a contingency in place in the case that our series sponsor exited before the original term of the contract. The decision came down to either the racers never getting paid or the racers getting paid late. We opted to commit ourselves to paying back the racers, no matter how long it took. About two years later, the IDRC paid off the remainder of the $290,000 in championship funds that were awarded for the 2002 and 2003 season. ”

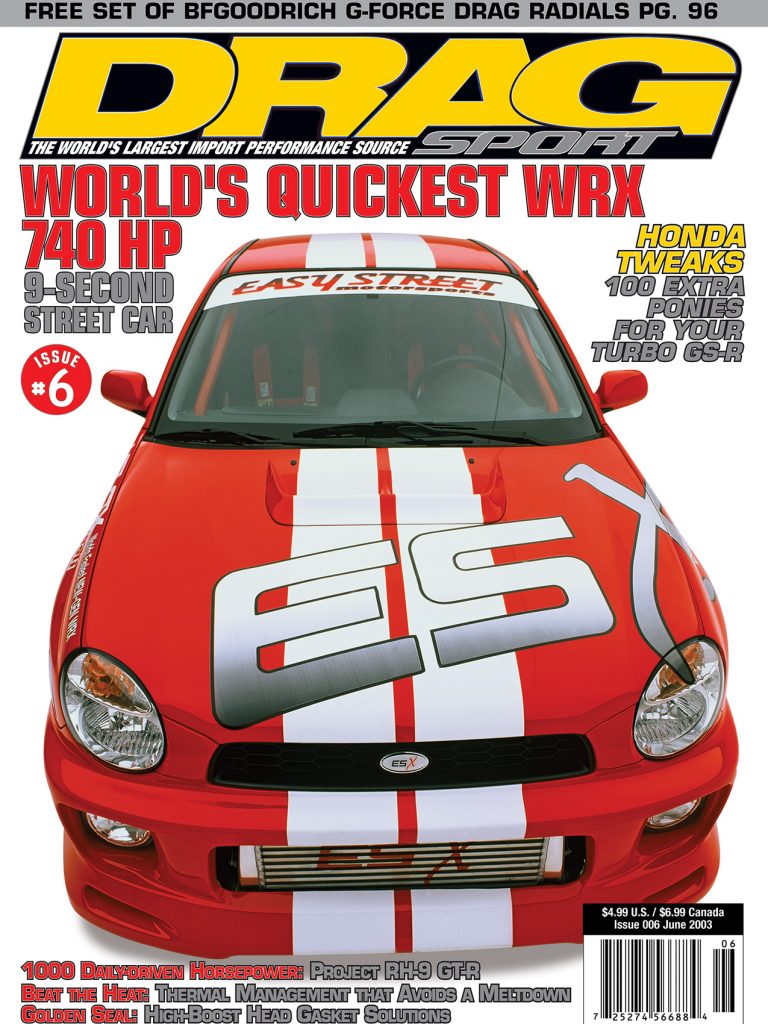

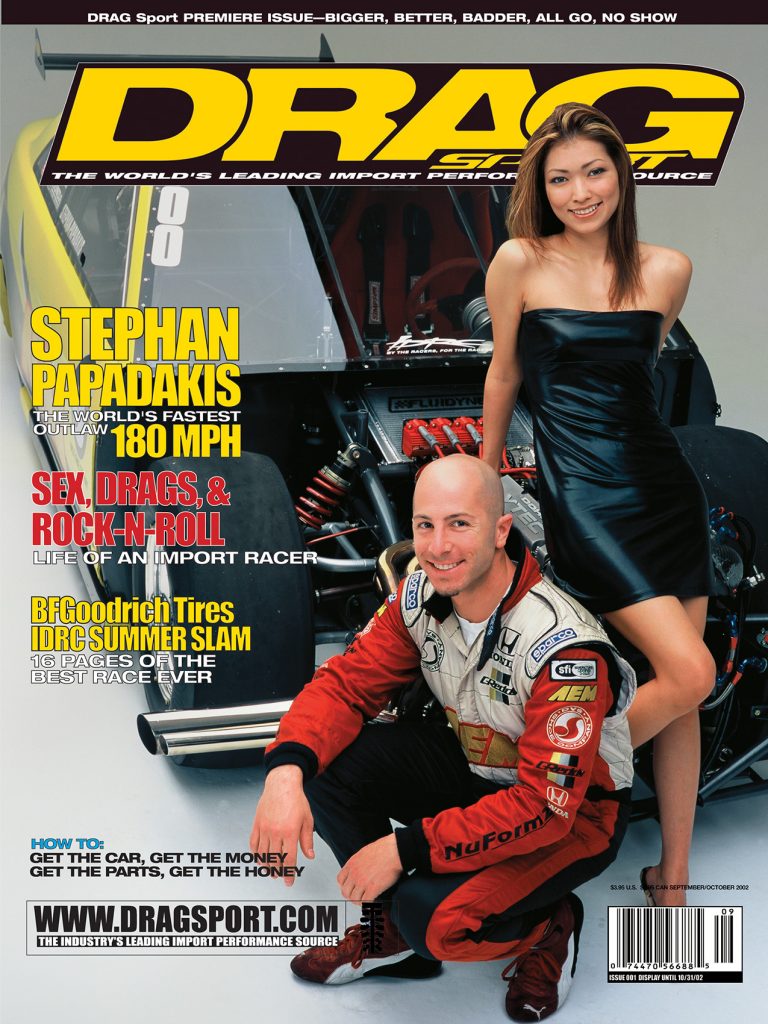

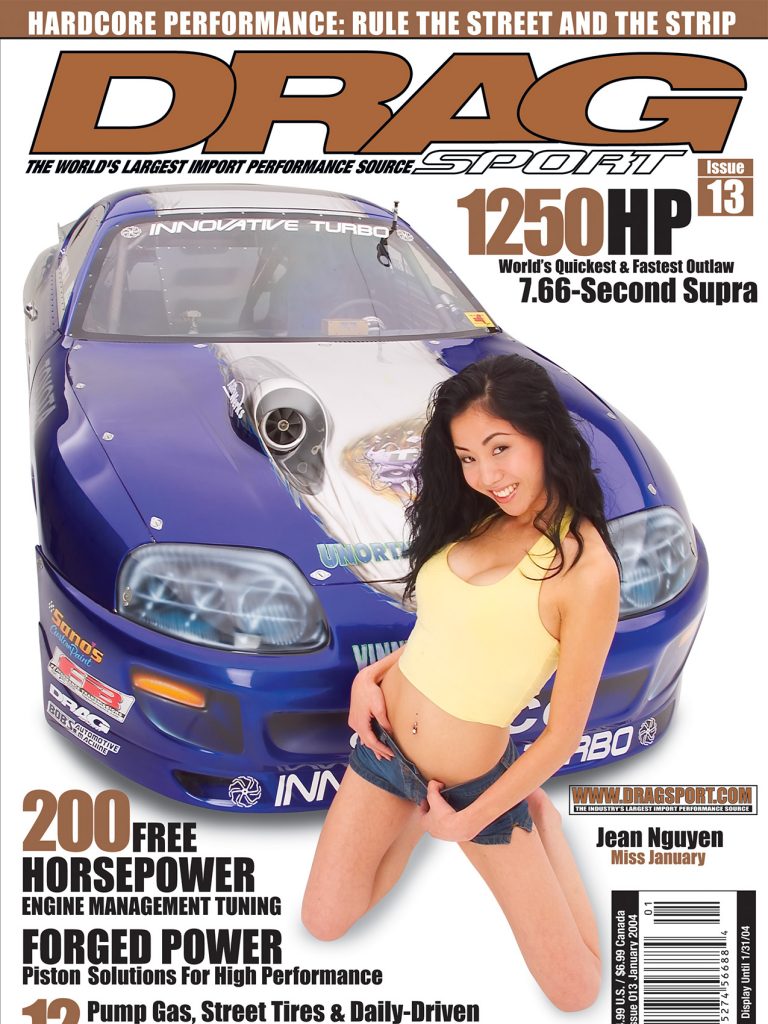

The IDRC climb back from the abyss was supported in large party by the unprecedented success of DRAG Sport. In issue one, we showcased one of the most well-known and well-liked import racers, Stephan Papadakis, (with model Ally King). The success of issue one prompted the first improvement for DRAG Sport, as we increased package size and added color pages to the entire book for issue two. In addition to the production quality increases, issue two marked the first triple-cover ever in automotive publishing, as all three stars of the Venom Racing team were featured (with model Brooke Kanno): Grant Downing, Jimmy O’Connor and Bruce Mortensen. Issue three marked the last of the original tabloid-format issues of DRAG Sport. Gracing the cover was the world’s quickest street-tire import, the VeilSide R-1 R32 GTR (with model Roni K). Issue four (Ron Lummus/Kim twins) marked three very important changes for DRAG Sport. First, the magazine changed from a newsprint-type, tabloid format to a glossy, Super “B” size format that was very newsstand friendly. Second, the frequency of the book changed from bimonthly to monthly. Third, the distribution focus shifted to national newsstand sales. Issues five (JJ Olson/Kim Chun), six (Ali Afshar), and seven (Bisi Ezerioha/Linda Tran) continued to feature the top pro racers in their respective classes. Issue six became a unique issue for us due to the absence of a cover model. Issue seven earned a another trivia mention as the last issue to feature the actual racer with the model on the cover.

While 2003 served as a year of success for DRAG Sport, the Big Three (Sport Compact Car, Import Tuner and Super Street) saw significant drops in subscriptions and single-copy sales. According to a FasFax analysis, the three titles lost between 10 to 15-percent of their subscriber base while singlecopy sales slid between 10- and 17-percent. Ironically, advertising rates for the PRIMEDIA titles continued to rise. PRIMEDIA advertisers paid considerably more fewer eyeballs than ever before.

DRAG Sport Becomes DSPORT

It was time for someone to step up and fight back against the bully known as PRIMEDIA. We decided that the best weapon in our arsenal would be our publication. Taking DRAG Sport to a broader audience meant changing the format to a standard newsstand magazine and expanding the content to focus on street performance vehicles. To broaden the potential audience, the magazine dropped “DRAG” from its title and became DSPORT. Depending on whom you ask, the first issue of DSPORT is either issue 13 (Vinny Ten, Jean Nguyen) or issue 14/15 (Erick Aguilar/Francine Dee). Issue 13 marked the beginning of the new editorial focus, and the page folios were changed from DRAG Sport to DSPORT, while the front cover logo remained DRAG Sport. By issue 14/15, there was no mistake that DSPORT was on the scene. The new logo was in full force.

ISSUES #14/15-to-#63 DSPORT Logo Version 1.0

DSPORT Strikes Back

In 2004 and 2005, DSPORT looked for new partners and avenues to grow its readership and continue its success. The June 2004 issue (#18) was the first issue distributed by Curtis Circulation. Curtis Circulation, the nation’s largest newsstand magazine distributor, helped to nearly double the sales of DSPORT overnight. The January 2005 issue marked the first-ever DSPORT calendar. The 2005 Calendar was polybagged with the magazine, and sales for that issue increased 80-percent compared to the previous issue. DSPORT found polybag success once again seen with the August 2005 “Tuner Savings Guide.” The 2005 “Tuner Savings Guide” provided a coupon and discount booklet from some of the top manufacturers and tuners in the industry. As DSPORT continued to grow, PRIMEDIA titles continued to struggle. Circulation figures for competitive PRIMEDIA titles fell 20 to 35- percent. Once again, advertisers and manufacturers in the industry were forced to bear the burden with rising advertising costs from the PRIMEDIA titles. Instead of looking at ways to improve its products, PRIMEDIA blamed its lack of performance on the state of the import performance community. In reality, a large percentage of the readers who were loyal to Super Street, Import Tuner and Sport Compact Car found other magazines that better met their needs.

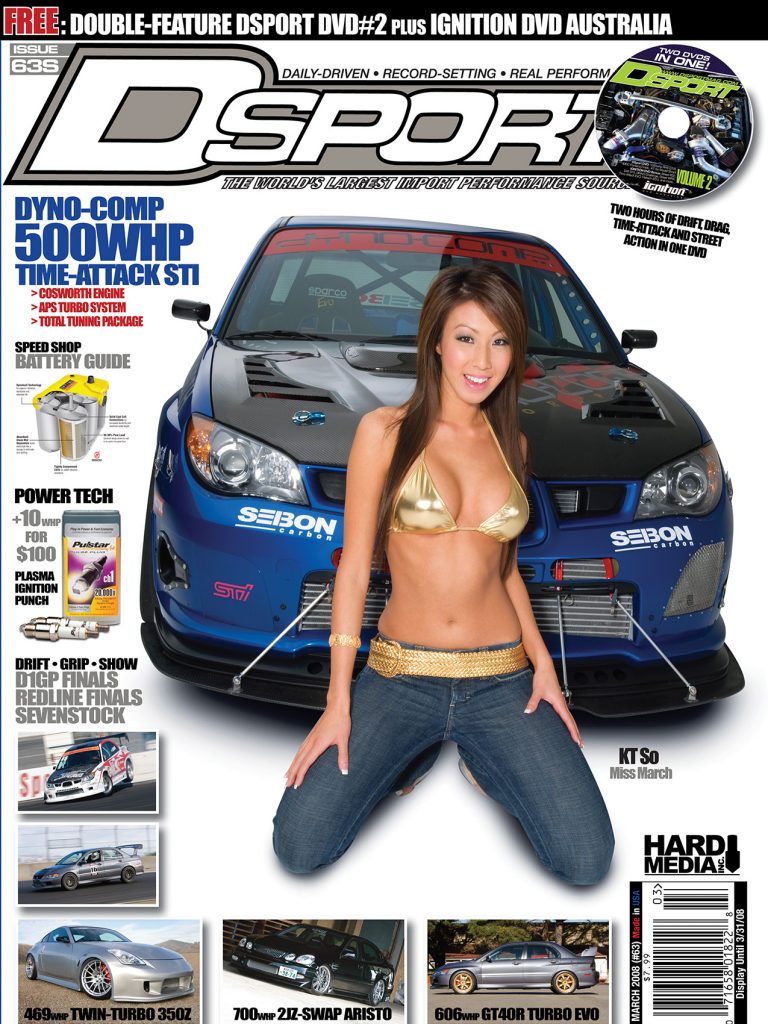

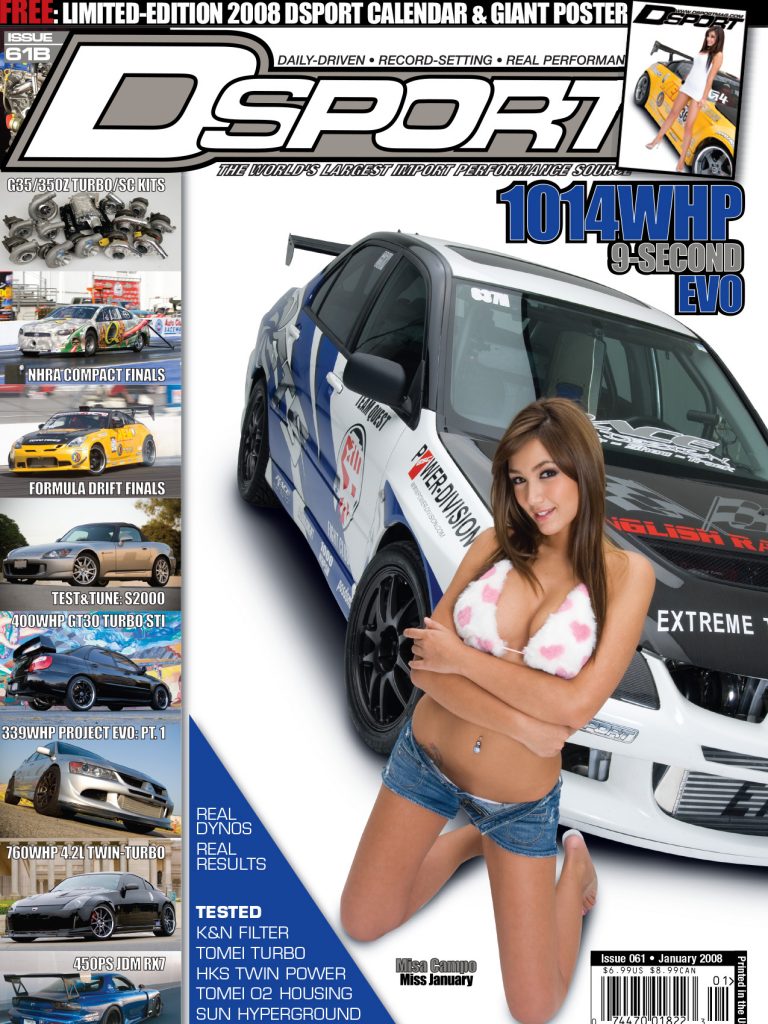

By 2007, an already inbred industry consolidated further when PRIMEDIA sold its entire Enthusiasts Media Group to Source Interlink Media. Meanwhile, DSPORT continued to brave the cold, scary world of publishing alone, increasing page counts and printing on the highest quality paper in the industry while its competitors cut staff, quality, and pages. Was providing the best magazine in the industry enough? Apparently not, DSPORT set its sights on producing the best DVD devoted to import tuning as well. DSPORT DVD issue #1 appeared in the fifth anniversary issue (#57, September 2007). Since then, DSPORT has produced sixteen more DVDs, each one filled with more racing action, technical information, feature cars, and top models.

ISSUES #64-to-#158 DSPORT Logo Version 2.0

NHRA Call it Quits

Moving on to 2008, the NHRA called it quits on its NHRA Sport Compact racing series as both participant and spectator attendance was horrible in 2007, despite record-setting performances. Apparently, the importperformance community could care less if a GM “sport compact” product could set records. They’d rather see cars they would actually think about owning in competition. By the end of 2008, bailouts, TARP and a soon-to-be implemented stimulus plans would either cripple or save (depending who you ask) the US economy which really started to skid. Once again, small businesses felt the squeeze.

Turbo, SCC and SORC Fold

By the time the January 2009 issue of DSPORT hit the stands, Turbo magazine was dead. In his Pub Note, Publisher Michael Ferrara predicted SCC would be next and by the following month the prediction was true. A few issues later, Source Interlink would put Michael Ferrara on legal notice for predicting that SORC would soon be bankrupt. Of course, it’s not illegal to tell the truth about a failing company and less than 60 days after the predication SORC would soon file bankruptcy, proving the prediction correct.

To be sure that DSPORT was reaching every enthusiast possible; a massive newsstand expansion took place during a time when every other magazine was cutting copies. The $700,000 gamble paid off as DSPORT took over the newsstands and markets previously held by competitive titles. As 2009 came near its end, the import-performance community would lose one of its greatest talents with the passing of Shaun Carlson.

ISSUES #159-to-Present DSPORT Logo Version 3.0

‘10, ‘11 and Beyond

Thanks to our readers and advertisers, DSPORT continues to succeed in a difficult environment. The passing of Turbo and SCC, two once great magazines, along the way shows how challenging the publishing industry can be. But, our readers can remain confident that DSPORT will not sell out to one of the media conglomerates. We will continue to provide you with the most reliable technical information, sickest cars, best advice, hottest girls, and highest-quality printing. That won’t change. DSPORT was engineered to serve its readers and the import-performance community. In doing so, DSPORT’s ultimate goal is to become the biggest automotive magazine in newsstand sales. To realize this goal, we will do whatever it takes.