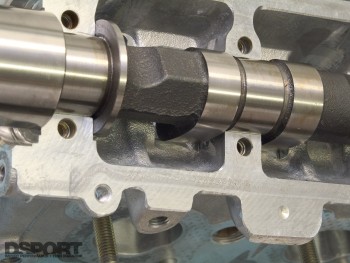

In our last installment of Ported & Flowed (October 2004), we mentioned that our next step would be to put the computer model to the test. This test would occur when we installed the ported cylinder head along with the camshafts on our GT-R. Then we would optimize the fuel and ignition curves for the new setup. The question that this exercise would answer is “Will the real-world numbers match the computer prediction?”.

Text & Photos by Michael Ferrara

Commentary by Allan Lockheed

The Computer Prediction

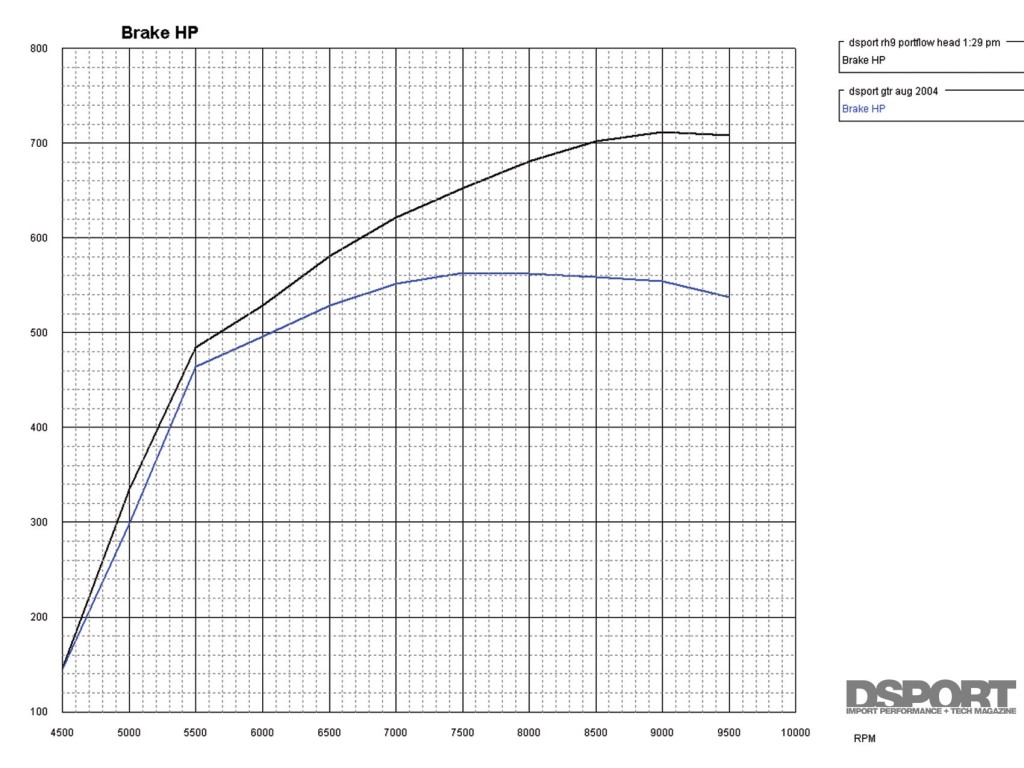

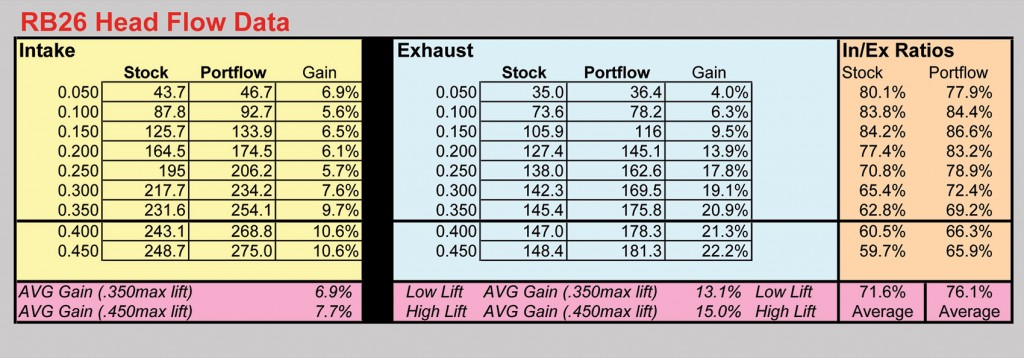

While we still had the engine set up with the factory heads and cams, the Engine Analyzer Pro software predicted that we should have 560 horsepower at the flywheel. At that time, we measured 505 horsepower at the wheels (a difference of 10%). The Engine Analyzer software also predicted that the ported cylinder head and bigger camshafts would generate 710 horsepower. Using the same percent loss between the software and the dyno, we should have seen 640 horsepower at the wheels on the dyno if the software was able to make an accurate prediction of the gains from the addition of the ported head and cams.

Our Gut Feeling

While we would have loved to see a 135 horsepower increase at the wheels, we doubted that the increase would be on that magnitude. Our gut was influenced by a number of factors. First, we were still going to be using 91-octane pump gas as our test fuel. Due to its low octane, we believed that we were going to encounter knock before getting close to this level of power. Second, the computer simulation was telling us that we were going to see over a 25- percent increase in peak power. That seemed a bit high in our estimation.  While we could see that gaining an extra 1000 rpm of power band and moving the peak rpm power up by the same amount would be worth about a 12-percent increase, we were skeptical as to where the other 13-percent would come from. The improved flow characteristics of the cylinder head and the higher valve lifts might take the total gain close to 20-percent, but 25-percent more horsepower just sounded too good to be true. Third, let’s remember that this engine is only 2.6-liters. If we were to generate, 640 horsepower at the wheels, that would mean that we were producing 750 horsepower at the flywheel. Cranking the numbers, that translates into producing 290 horsepower per liter. That’s a power figure that just sounded out of reach for an engine drinking 91-octane. Obviously, we were skeptical of the computer simulations optimistic predictions.

While we could see that gaining an extra 1000 rpm of power band and moving the peak rpm power up by the same amount would be worth about a 12-percent increase, we were skeptical as to where the other 13-percent would come from. The improved flow characteristics of the cylinder head and the higher valve lifts might take the total gain close to 20-percent, but 25-percent more horsepower just sounded too good to be true. Third, let’s remember that this engine is only 2.6-liters. If we were to generate, 640 horsepower at the wheels, that would mean that we were producing 750 horsepower at the flywheel. Cranking the numbers, that translates into producing 290 horsepower per liter. That’s a power figure that just sounded out of reach for an engine drinking 91-octane. Obviously, we were skeptical of the computer simulations optimistic predictions.

On the Dyno

In tuning for the new combination, we decided to start at a lower boost level than we ran with the “un-ported” cylinder head and stock cams. With the “un-ported” head and stock cams, we set the maximum boost pressure to 1.50kg/cm2 (21.3psi). For our first set of runs on the dyno with the ported head and bigger cams we set the boost pressure to 1.30kg/cm2 (18.5psi). In tuning for the new setup, we quickly found that the engine now had a different personality. For one, the engine definitely needed more fuel than before. Of course, this was expected as the power output was considerably more. With regards to fuel, we also noticed another pattern. The engine seemed to not lose as much power as before with richer fuel mixtures. This led us to believe that the changes that we made must have improved the mixing characteristics of the air and fuel within the combustion chamber. With regards to ignition timing, we again saw evidence of this improvement. Our engine now required less timing for peak power. When an engine requires less timing to produce peak power, it is a direct indicator that other factors have increased the flame velocity within the cylinder. When the type of fuel and inlet air temperatures are constant, the most likely factor to increase the flame velocity is an improved mixing of the air and fuel within the cylinder. After a few pulls on the dyno, we were surprised to see that we had already hit 581 wheel horsepower at 8400 rpm.

In tuning for the new combination, we decided to start at a lower boost level than we ran with the “un-ported” cylinder head and stock cams. With the “un-ported” head and stock cams, we set the maximum boost pressure to 1.50kg/cm2 (21.3psi). For our first set of runs on the dyno with the ported head and bigger cams we set the boost pressure to 1.30kg/cm2 (18.5psi). In tuning for the new setup, we quickly found that the engine now had a different personality. For one, the engine definitely needed more fuel than before. Of course, this was expected as the power output was considerably more. With regards to fuel, we also noticed another pattern. The engine seemed to not lose as much power as before with richer fuel mixtures. This led us to believe that the changes that we made must have improved the mixing characteristics of the air and fuel within the combustion chamber. With regards to ignition timing, we again saw evidence of this improvement. Our engine now required less timing for peak power. When an engine requires less timing to produce peak power, it is a direct indicator that other factors have increased the flame velocity within the cylinder. When the type of fuel and inlet air temperatures are constant, the most likely factor to increase the flame velocity is an improved mixing of the air and fuel within the cylinder. After a few pulls on the dyno, we were surprised to see that we had already hit 581 wheel horsepower at 8400 rpm.