A Closer Look – Valve Timing

In this simplified explanation, if we only look at lift and duration, we only know how high a valve is lifted and for how long. What lift and duration fail to tell us is when the valves are opened and closed.

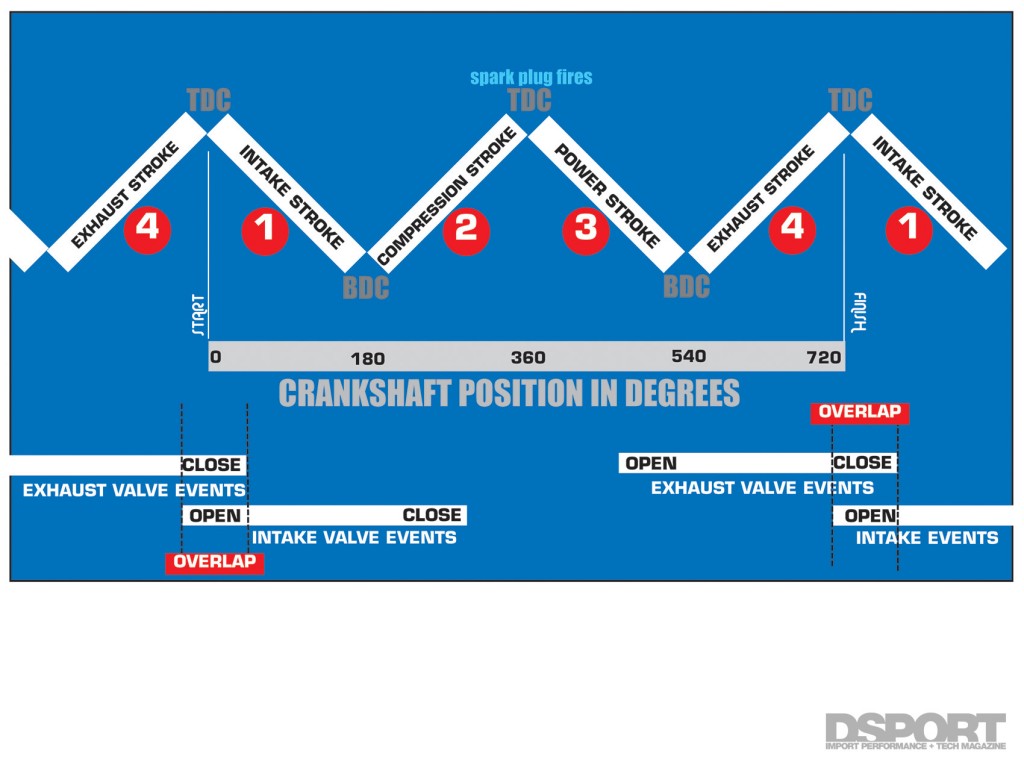

Knowing that the complete fourstroke cycle contains 720 degrees of crankshaft rotation, and that the intake stroke (the piston moves down the cylinder when the intake valve is open) makes up one fourth of the cycle, it can be easily deduced that the theoretical duration of the intake cycle is 180 degrees (one fourth of 720). If we could instantaneously open the intake valve at Top Dead Center (TDC, the beginning of the intake stroke) and have the intake charge immediately start flowing into the cylinder until the piston was at Bottom Dead Center (BDC, the end of the intake stroke, 180 degrees later) where the intake valve would instantaneously slam shut, we might have an engine that would run well with only 180 degrees of intake duration.

Knowing that the complete fourstroke cycle contains 720 degrees of crankshaft rotation, and that the intake stroke (the piston moves down the cylinder when the intake valve is open) makes up one fourth of the cycle, it can be easily deduced that the theoretical duration of the intake cycle is 180 degrees (one fourth of 720). If we could instantaneously open the intake valve at Top Dead Center (TDC, the beginning of the intake stroke) and have the intake charge immediately start flowing into the cylinder until the piston was at Bottom Dead Center (BDC, the end of the intake stroke, 180 degrees later) where the intake valve would instantaneously slam shut, we might have an engine that would run well with only 180 degrees of intake duration.

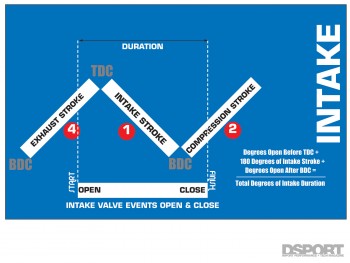

Early Intake Valve Opening

In practice, there are many advantages to opening the intake valve early and closing it late. By initiating the opening of the intake valve early, the intake valve has time to get to a lift where considerable flow will begin. On a well-designed cylinder head teamed with a free-flowing exhaust, the pressure in the cylinder, when the valve is opened early, may be lower than atmospheric, so the intake charge actually gets sucked in (in practice, the exhaust valve is still open when the intake valve begins to open). The benefits of early intake valve opening are very rpm dependent. At low engine speeds, extremely early intake valve opening may cause exhaust gasses to enter into the intake manifold causing erratic idle and other problems. At higher engine speeds, this same amount of early intake valve opening will have no adverse effects since the intake manifold is not operating under a vacuum condition.

Late Intake Valve Closing

Now that we understand why we need to open the intake valve early, let’s take a close look at the closing of the intake valve. The reason we leave the intake valve open past BDC is inertia: Objects at rest tend to stay at rest, objects (or a mass of air in this case) in motion tend to stay in motion. Since we have an intake charge in motion, we can experience additional filling of the cylinder while the piston dwells (or remains in place) at the bottom of its stroke at BDC. Depending on the rod ratio of the engine, the piston may dwell around BDC for 20 degrees of crank rotation before the piston starts to move up the cylinder. During this time the flowing intake charge continues to fill the cylinder.

If the intake valve closes too late, the piston may pump some of the intake charge out of the cylinder through the intake valve and back into the intake manifold. This reverse flow is obviously undesirable, and as you may have guessed, the optimum closing of the intake valve is also very rpm dependent.

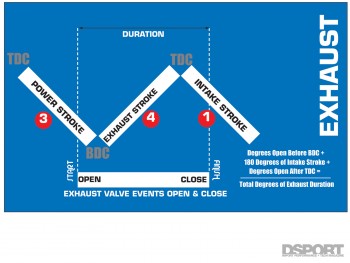

Exhaust Valve Open Early

The major difference in dealing with the exhaust side is that the average pressure in the cylinder is probably more than six times the average pressure during the intake cycle. This makes the task of releasing the exhaust gasses easier than trying to get the intake charge into the cylinder.

The major difference in dealing with the exhaust side is that the average pressure in the cylinder is probably more than six times the average pressure during the intake cycle. This makes the task of releasing the exhaust gasses easier than trying to get the intake charge into the cylinder.

During the power stroke, the majority of horsepower is generated during the first 90 degrees, or first half of this 180 degree cycle. This being the case, opening the exhaust valve early has little effect on killing power. In fact, power is usually increased. Since the residual pressure is released from the cylinder, the piston doesn’t work as hard to push the remaining gasses out when it begins its upward movement on the exhaust stroke.

Exhaust Valve Closing Late

Keeping the exhaust valve open after TDC can also have benefits. If the exhaust valve is kept open after TDC, the intake valve will also be open at the same time. Both intake and exhaust valves are open at the same time is called “valve overlap.” The ideal amount of overlap depends on rpm. Higher rpms tolerate more overlap, and the intake charge can be drawn into the cylinder due to the draft caused by the exhaust gasses leaving the cylinder. When overlap gets excessive, exhaust gas can make its way into the intake manifold, diluting the intake charge. A diluted intake charge limits power production, so a careful balance must always be struck.